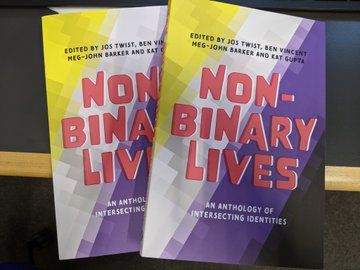

Last April (2020), an anthology of essays by thirty non-binary people was published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers under the title Non-Binary Lives, edited by Jos Twist, Ben Vincent, Meg-John Barker, and Kat Gupta. This is my chapter from that book.

Introduction

I have never felt totally comfortable in the spaces or boxes into which being assigned male at birth (AMAB) automatically put me. I pretty much always knew I was queer, but didn’t find any particular connection with gay men. I went to an all boys school, but didn’t really fit in. I look very masculine but don’t feel it. I shudder at the inevitable association that my physical embodiment creates with toxic masculinity. People see me and make assumptions about the person that I am. That is made more complex by being what I often refer to as an ‘outside insider’, a queer radical who lives their life at the very heart of the British establishment with all the inevitable privilege that comes with it. I bet there are very few non-binary people who have found themselves over the years deep inside two of Britain’s main political parties; the Freemasons; the Judiciary; the City of London; faith communities; London private members’ clubs; major charities; the board of a FTSE listed plc; and some of the U.K.’s top sporting bodies. This is my story.

Schooling in masculinity

My old school sits in the heart of a rather dreary Lancashire industrial town ten miles north of Manchester. It was the centre of my world for fourteen years, from arriving in kindergarten aged four to being spat out aged 18. Like so many of those types of independent grammar schools, it was intensely gendered. From the age of seven upwards, I was part of the boys’ school, separated by a street (which might as well have been an ocean) from the girls who had been my kindergarten class mates. I was taught by an almost exclusively male staff (the few women teachers were addressed as ‘sir’!) in a very male dominated environment where sport and the cadet force were the principal extra-curricular occupations. Those of us who were more attracted to drama, music, politics and debating, were definitely in the minority.

It was in this environment that I discovered my sexuality, or certainly that aspect of it that was attracted to masculinity. It was also clear that this attraction was to softer masculinity, whilst at the same time feeling alienated by the robust laddish nature of the more mainstream cohort in the school. Reflecting back on it now, I was hugely put off by the primal instincts of the other boys, often egged on by the schoolmasters – the need to win, to be the best, to be strong, to not show emotion, to never admit to being a victim. This was my initial exposure to what I now know of as toxic masculinity, and I didn’t like it. But, counter to those schoolmasters’ aspirations, their toxic masculinity never made a man of me, being able to be an authority figure with kindness gave birth to the person I am.

I found my sense of self by becoming a somewhat larger than life character at the centre of school activities: writing for the school magazine, taking leading roles in school plays, acting as scorer for the 1st XI cricket team, being the often knock-about star attraction in the debating society. During my final year at school, as a prefect, I set out to protect those boys who were picked on for being outside the mainstream: those of minority faiths and ethnicities, the players of chess or Dungeons and Dragons, and the boys who were probably queer even if they didn’t know it yet. Life at school was tough, but it did help me to become the person I am today, engraining in me some of the values that have found a voice in more recent years. It was also the start of the journey that led me into public service, of which more later.

Student life and the gay straight-jacket

Arriving at the University of Essex in October 1990 was liberation. Not only was it some considerable distance from home, but it also enabled me to explore my self-assumed sexuality as a gay man. My only sexual experiences up until that point had been with other boys at school, and only then secretly in hidden corners of the campus. So, on my second night, I found myself at a freshers’ disco in the Union in the arms of a beautiful guy, the first time I had been able to kiss a man in public and it was electric. Coming out as gay was liberation, but it also became, ironically, a straight-jacket.

Being in a co-ed space for the first time also exposed me to the ‘opposite’ sex and that became a revelation. I was not only attracted to men. Indeed, thanks to the determined pursuit of a fellow student who re-took my virginity, I discovered that I also very much enjoyed exploring a woman’s body. What was also clear though was that my taste was for those women who were less conventional, especially if presenting as more masculine of centre. Unfortunately, however, the political dynamic in queer communities at the time was very binary – you were gay, or you were straight – bisexuality was not an option, nor were they particularly welcoming spaces to trans people, not that there was much trans visibility back in the early 1990s.

This became even more apparent when, on graduation in 1994, I was elected to the national executive of the National Union of Students (NUS) and attended my first LGB campaign conference. In fact, it was the first ever LGB conference. Up until that point the NUS campaign had been steadfastly Lesbian & Gay, and it was clear that bi people remained unwelcome – there was vituperative talk of ‘breeders’ and the women’s caucus had morphed into a lesbian only space. Suffice it to say that any mention of trans people was greeted in an even more unfriendly manner. In such an environment it became clear that I should keep very quiet about my growing sense of attraction to some women and certainly never entertain any questioning of my gender identity.

Pride and prejudice

Life immediately after NUS remained focused on queer community. Early in 1996, I joined the board of the Pride Trust, the then organisers of the London Pride march and festival, which had just become LGBT Pride rather than Lesbian & Gay. The change of name was however superficial, and hostility remained towards both bi and trans people – Pride’s women’s advisory group, for instance, resolved that trans women were not welcome in the women’s tent at the festival. And yet, despite their refusal to include both bi and trans folk, it was some of these lesbians that I found myself drawn to emotionally and physically.

The soft masculinity and humanity of many butch lesbians drew me in at the same time as I felt increasingly distant from gay male culture. I think a substantial part of this attraction came from the more collaborative and collective behaviours and politics of many lesbians, which contrasted harshly with the individualistic and rather self-centred and self-absorbed nature of quite a lot of gay men, as well as the misogyny which so many gay men did (and still do) exhibit. I remember an article in the Pink Paper by a lesbian activist expressing anger at the absence of reciprocity from gay men to back issues facing lesbians despite all the efforts that lesbians had put in to, for example, the campaign to support those living with HIV/AIDS and the fight to equalise the age of consent for men who have sex with men. That truth really hit me, and made me feel desperately awkward about being, because of my body, identified with such a selfish gay male world. I so deeply wished that I hadn’t been born male.

A very personal experience of the difference between gay male and lesbian realities came when I was dumped by my then boyfriend in the centre of Soho late in 1996, leaving me heartbroken and frightened. Not one of my gay male friends was available or seemingly interested in being there for me in my moment of need. But one of my closest lesbian friends, Rachel, and her partner Jo, dropped everything to take care of me that night. I felt so incredibly lucky to have such supportive people in my life. Rachel and Jo remain two of my closest friends to this day.

The gender question and coming out as bi

My experience of the disparity in approach between queers of different genders was so stark, it made me begin to question whether I was being constrained by the physical body I inhabited. I certainly felt much more like the lesbians I was close to than many of the gay men I knew. And that was often remarked on by friends who said that I seemed like a fellow lesbian trapped in a gay man’s body. Well perhaps I was? I started to wonder whether my attraction to butch aesthetic was actually more that I might be one of them rather than simply wanting to ‘be with’ them. Certainly, in my mind’s eye, I allowed myself to fantasise about being a soft butch with short floppy hair who was loved and protected by stronger masculine presenting women. My female persona even had a name, Alex.

At the time though, in the mid-late nineties, there was very limited information or support for people who were contemplating their gender, and the possibility of someone male assigned at birth transitioning to be anything other than a hyper-feminised woman was impossible under the strictures of the Gender Identity Clinic at the time. In any case, I don’t think I was anywhere near wanting to take such life-changing steps, especially given the very clear negativity that I had already experienced in lesbian and gay circles about trans women. The idea of transitioning only to be rejected by those I wanted to feel loved by remains too horrible to contemplate.

What also made it difficult was that my career was starting to move forward and whilst being out as a gay man was just about acceptable, announcing to the world that I was bi, or that I had some ‘wacky’ idea about my gender, was really not going to cut it, either at work or with my lesbian and gay friends. Indeed, I did not come out as bi until I was in my early thirties after I fell in love with my first girlfriend, herself someone who, as a Stonewall staffer, had adopted a lesbian identity due to the hostility towards bi people in that workplace. That was not easy, and indeed some of my friends, both lesbian and gay, rejected my new bi identity, with one in particular cutting me out of their life.

Out in the establishment

As my career developed, and I became more engaged with various aspects of the British establishment, it became harder to confront what remained an ongoing question in my own mind about my gender. More and more I was antagonised by toxic masculinity – both gay and straight – in the worlds of work and my voluntary and community activity, but more and more I felt like I didn’t know how to respond.

In 2001, I was elected as a Common Councilman of the City of London, an ancient and highly gendered title which is essentially a local councillor, and the toxicity of the place was palpable. At 29 I was the youngest elected member of the Council and I was clearly unwelcome. The average age of my colleagues was over 70, and the vast majority were male and often boarding school educated. Privilege was everywhere as was prejudice. Jokes about ‘queers’, ‘blacks’, and women were still the order of the day for some councillors. Bigotry was built into the culture of the place, with members being instructed that they must only bring guests of the ‘opposite sex’ to Council functions. The arrival of a young outwardly gay man with progressive ideas was a red rag to a very large bull.

Over the eighteen years that I have served as a City councillor, the officially sanctioned prejudice has decreased and many more younger City councillors have been elected, advocating for change and determined to see it happen. I am now quietly hopeful but recognise that some of the behaviours remain toxic; an undercurrent of bullying and backhanded comments still exists, and when challenged often attract a ‘man-up’ style response, such that it took me until the middle of 2018 to begin coming out about being non-binary.

But change is slow. Only recently, I was told by a senior colleague that I displayed too much emotion and shouldn’t take things so personally. Another man also ‘advised’ me to drop any public reference being non-binary and that he certainly wouldn’t refer to me using ‘they’ pronouns.

Despite this, there has been progress both personally and institutionally. For example, in 2017 we finally succeeded in getting the rainbow flag hoisted at Guildhall for Pride week. As of 2018, I chair the workforce committee and lead on diversity and inclusion, including heading up a policy review on gender identity and trans inclusion, although that led me to be publicly outed as non-binary in the Sunday Times.

Elsewhere in my career, I have been at the forefront of tackling discrimination. Perhaps most visibly was in 2014 as a member of the Football Association’s (FA) inclusion advisory board where I was the only member willing to speak out publicly when football’s most powerful administrator was caught sending incredibly sexist emails to colleagues. It seemed remarkable to me that the FA refused to take action against a man so clearly in breach of the game’s anti-discrimination rules dismissing it as either ‘a personal matter’ or ‘just banter’. Of course, in the culture of football, had the email content been racist, he would have been out of his job the next day, but somehow sexism was acceptable. This was toxic masculinity at its worst, and I challenged it, and in return I was sacked, for speaking truth to power. Whilst football may not have liked what I said, a letter published in the Daily Telegraph supporting my stance was signed by 28 leading equality campaigners, politicians, and sport officials.

Perhaps the oddest aspect of my activism has been in Freemasonry. The obvious question is why would someone as passionate as me about diversity become a Freemason? Well, the answer is because I made a promise to my dying step-grandfather. But then why stick with an organisation which is so institutionally sexist? First, I think that, despite its sexism, it actually does some good. The values espoused by Freemasonry chime with my own: integrity, kindness, honesty, and fairness. Equally, the Masonic obligation to charity through education, healthcare, and care for older people, mirrors my own commitment to public service. Also, other than gender, its membership is actually remarkably diverse certainly based on race, religion, sexual orientation, disability and even class, regularly bringing together people from differing backgrounds who might otherwise never meet.

That said, it is an institution which clearly needs to change, and I have tried to use my position, as a high-profile member, to encourage that change from the inside. In my valedictory address on standing down as chair of one of Freemasonry’s national committees in 2017, I demanded wholesale cultural change. I said that the male Grand Lodge of England should formally acknowledge that many thousands of women are Freemasons and recognise the lodges they belong to. I called for a change in male Freemasonry’s misogynistic language and anachronistic approach to gender roles in society. I said that the overly hierarchical structure that can lead to bullying must end and that Freemasonry should more openly acknowledge that it has many members who are gay and bisexual. It has taken a while since that speech, but some of those changes are now happening.

Finding myself

After so many years of fighting the inner demons of toxic masculinity and campaigning to change the culture in several major institutions, it has only been in the last few years that I have really begun to readdress the issue of my gender. And that was significantly influenced by being with my then partner as I supported them through their own gender journey. Had I not been with MJ, learning alongside them, the concept of being non-binary may not have felt like an identity that I could adopt, and I am enormously grateful to them for being my guide and my mentor, and for the love we have shared.

Even with that support, I still fear that my presentation is too masculine, not queer enough, not genderqueer enough to be accepted and ‘pass’ as non-binary. By way of example, at a recent Stonewall conference session on non-binary gender, the highly feminised appearance of the two AMAB enby presenters made me feel particularly dysphoric.

I have to keep on reminding myself that my gender is what is in my head, and not measured by the way I (or others) appear. Despite still feeling very much like the soft butch of my earlier dreams, I no longer want to change my body. In fact, since growing a beard and accepting my presentation as a big queer bear, I have been a lot happier with the body I inhabit, and grateful that it is often recognised as genderqueer. Indeed, what has also been wonderfully affirming is the number close trans and non-binary friends who proactively say that they ‘see me’, with one saying that he knew from the moment that we met that I wasn’t a cis guy but rather a fellow trans person, another who calls me their butch, and another their dykey-bear.

Nonetheless, the intellectual concept of my gender remains a challenge, not least because I know that to most people I do still appear as a man. And I recognise fully that I have grown-up with and still receive male privilege, which I try to check constantly. I’m also very aware that it is substantially because of this male appearance and the male privilege that comes with it, that I was granted access to the establishment which has allowed me to be the diversity advocate that I am.

But, at heart, I know that I am neither exclusively male nor female, but somewhere in between. A soft butch, presenting as a queer bear. Hopefully, eventually, the rest of the world may one day recognise that, even in the establishment.

Copyright © Jessica Kingsley Publishing and C. E. Lord, 2020